By 1970, project Apollo had sent four missions to the moon, two of which had landed on the Lunar surface. Apollo 13 was expected by all to be another routine mission to the moon and back, hoping to land at the moon’s Fra Mauro Highlands, with many scientists anticipating the mission to return “lunar soil [from] up to 10 feet below the surface…[and] access to material of four different ages.”1 However, these goals and hopes of new scientific discoveries would soon be dashed.

The Fra Mauro Highlands, captured by the Apollo 14 mission. Apollo 13’s scrubbed landing would have landed in this region. Credit: NASA, Wikimedia Commons.

Warning Signs

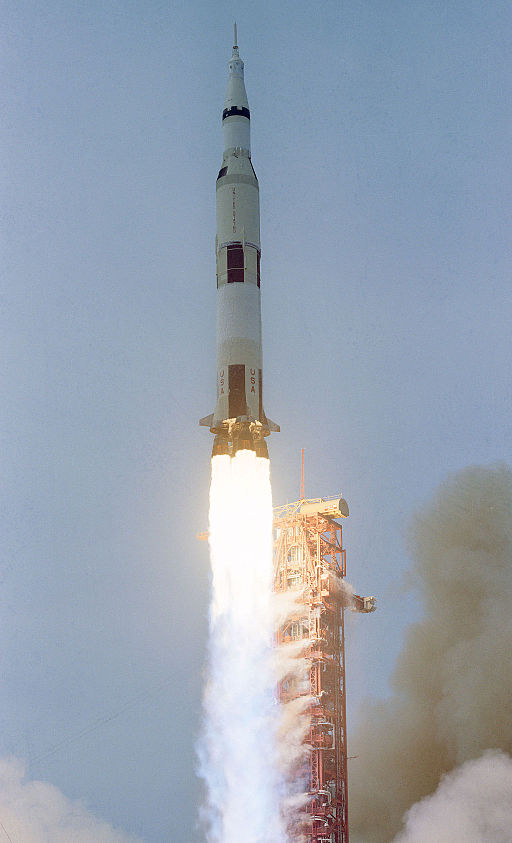

In the days leading up to the launch of Apollo 13, mission Commander Jim Lovell later admitted that in retrospect, there were “several omens that occurred in the final stages of the Apollo 13 preparation.”2 The first of these omens came in the form of a last-minute crew swap. Every Apollo mission included a “prime” crew and a “backup” crew. The prime crew was the crew originally scheduled for the flight, while the backup crew was trained alongside in the unlikely event any of the crewmembers would need to be replaced. Thomas “Ken” Mattingly, Apollo 13’s original command module pilot, had been exposed to rubella only two days before launch, necessitating a swap with backup Jack Swigert. Another worrying sign that Lovell also believes should have been noted was an oxygen tank with several discrepancies, most notably dropping in pressure at a faster pace compared to the others. However, as previous missions had been filled with technical glitches, this was noted but not followed up on. Apollo 13 would be cleared for launch on Saturday April 11, 1970, and would go mostly smoothly. During the launch process, one of the engines of the Saturn V moon rocket’s second stage cut-off early, but this issue “was compensated for by longer burns of the remaining engines.”3 Many back in mission control, and the astronauts, felt that the worst was behind, and settled in for what seemed yet another routine flight to the moon.

Image 1: L-R: Lovell, Mattingly, Haise (Credit: NASA, Wikimedia Commons)

Image 2: L-R: Lovell, Swigert, Haise (Credit: NASA Image and Video Library, Wikimedia Commons)

The Launch of Apollo 13 on April 11, 1970. At the time of publishing, the Saturn V rocket holds the record of being the only rocket to carry astronauts to the moon. Credit: NASA, Wikimedia Commons.

Lost Moon

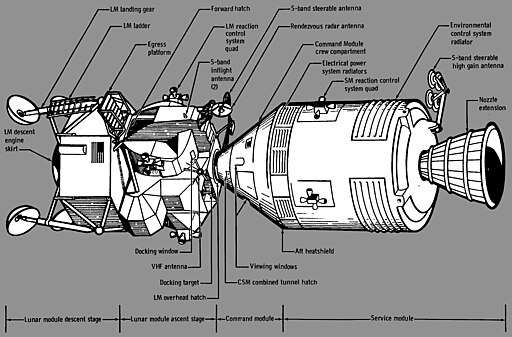

After an uneventful second day of the mission, “Apollo 13 was looking like the smoothest flight of the program.”4 However, April 13, 1970, would be anything but uneventful. Less than a day from lunar orbit, the crew would document their activities enroute to the moon in a television broadcast from their spacecraft. After documenting a ship that was smooth sailing, no one knew what would happen next. In a process that would recalibrate sensors in the spacecraft’s service module, an electrical fault caused a spark, causing the defective oxygen tank to explode and damaging another, as well as several key components necessary for operations, like two of the spacecraft’s three fuel cells, “our prime source of electricity.”5 Not only had they lost power, but the damaged oxygen tanks were leaking oxygen “at a high rate.”6 As it sunk in for the crew and NASA that the damage meant they had to abandon the moon, plans were made in order to bring the crew home, even if it meant pushing hardware past its limit. In order to survive, a plan was devised. The Lunar Module (LM), now useless with the scrubbed landing, would turn into a makeshift “lifeboat,” and a flight plan was made to allow the crew to land in the Pacific Ocean. This process wouldn’t be easy, however. The LM, which was designed for a 45-hour life span to support two astronauts. Now, “it was being asked to care for three men [for] nearly four days.”7

The Road Home

As preparations were made for the voyage home, national leaders on Earth soon became gripped by the mission’s events. President Nixon cancelled appointments in order to be updated on the mission, while Pope Paul VI lead prayers for the crew’s safe return at St. Peter’s Square, and even Soviet Premier Aleksei Kosygin wrote to the US government that “the Soviet Government has given orders to all citizens and members of the armed forces …to render assistance in the rescue of the American (Apollo 13) astronauts.”8 While the people on earth sent their well wishes to the crew, Apollo 13 made its closest approach to the moon, where astronauts Fred Haise and Jack Swigert “snapped photos like a couple of tourists.”9 After a successful burn that set them on a course home, Apollo 13 settled in for a safe journey home. Shutting down all non-essential electrical systems to conserve power, the crew would settle in for a very uncomfortable ride home, with temperatures dropping as low as 38 degrees Fahrenheit, making sleep “almost impossible.”10 But the cold was the least of their problems.

Improvise and Adapt

As the astronauts breathed their limited oxygen, they expelled Carbon Dioxide. Under normal circumstances, the danger of Carbon Dioxide was taken care of through filters. However, the makeshift lifeboat in the LM was not meant to have the number of astronauts that it was holding for twice its useful lifespan. During this time, carbon dioxide levels were reaching dangerous levels. Usually, this would require the replacement of the Carbon Dioxide filter, but the only spare filters were in the located in the Command Module. When the astronauts went to replace the filter, their struggles would only be compounded: the replacement filter was the wrong shape. The CM’s filters were square, while the LM’s were round. In “a fine example of cooperation between ground and space,”11 the crew would receive oral instructions to build an improvised filter using materials only on board, which brought the levels of CO2 to a far more manageable level.

Return to Earth

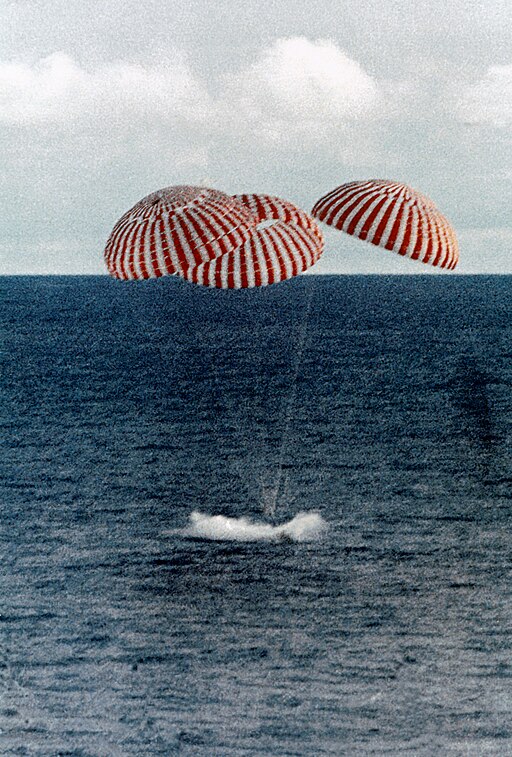

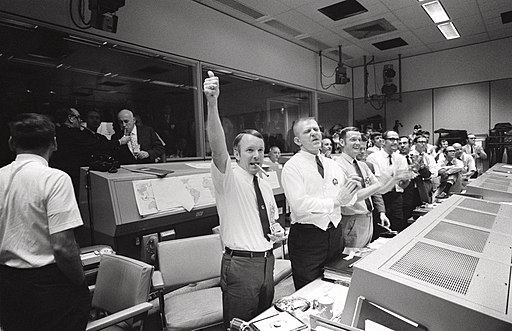

As April 17, 1970, approached, an air of uncertainty hung over mission control. Was the explosion’s damage worse than thought? Would keeping the Command Module powered down for as long as it was cause damage to vital systems for recovery? The only way to know was to see the damage. As the crew began powering up the Command Module, they would need to separate the Service Module in order to survey the damage. Upon separation, the full extent of the damage became obvious: “There’s one whole side of that spacecraft missing…”12 commented one of the crew. From the top to the base of the Service Module, an entire side had been blown off by the explosion, exposing internal components to the elements of space. After configuring for re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, the crew would close the hatch to the LM and began their plunge into the atmosphere. For nearly four minutes, the crew had no idea that “a billion people were following us on television and radio” 13 were waiting with bated breath for their safe return. Mission control and the world soon breathed a sigh of relief when radio contact was made, and the image of the Command Module descending on its parachutes were seen on television.

The New York Times editorialized that “Only in a formal sense will Apollo 13 go into history as a failure.”14 To this day, though it did not accomplish the goals it set out to do, NASA still considers Apollo 13 “The Successful Failure,” and many consider it their greatest success. Through the numerous challenges faced and overcome, three astronauts who were almost certainly doomed, returned home safely.

footnotes

- Everly Driscoll. “Apollo 13 to the Highlands.” Science News 97, no. 14 (1970): 353. https://doi.org/10.2307/3954891. ↩︎

- Lovell, James A. “Chapter 13: ‘Houston, We’ve Had a Problem.’” Essay. In Apollo Expeditions to the Moon, 247. Washington, D. C.: Library of Congress Cataloging, 1975. ↩︎

- “Apollo 13 – Houston, We’ve Got a Problem – NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS).” NASA. NASA, n.d. Accessed September 22, 2024: 6. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19700021741. ↩︎

- Lovell, James A. “Chapter 13: ‘Houston, We’ve Had a Problem.’” Essay. In Apollo Expeditions to the Moon, 248. Washington, D. C.: Library of Congress Cataloging, 1975. ↩︎

- Ibid, 249. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid, 257. ↩︎

- “Apollo 13 – Houston, We’ve Got a Problem – NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS).” NASA. NASA, n.d. Accessed September 22, 2024: 15. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19700021741. ↩︎

- Ibid, 17 ↩︎

- Lovell, James A. “Chapter 13: ‘Houston, We’ve Had a Problem.’” Essay. In Apollo Expeditions to the Moon, 262. Washington, D. C.: Library of Congress Cataloging, 1975. ↩︎

- Ibid, 257. ↩︎

- “Apollo 13 – Houston, We’ve Got a Problem – NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS).” NASA. NASA, n.d. Accessed September 22, 2024: 22. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19700021741. ↩︎

- Lovell, James A. “Chapter 13: ‘Houston, We’ve Had a Problem.’” Essay. In Apollo Expeditions to the Moon, 263. Washington, D. C.: Library of Congress Cataloging, 1975. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎