Often, events in history are studied separately, often as if they are in separate or even different worlds. However, this is hardly the case. Even if we study each event individually, there is always context surrounding events, and decisions taken that effect these events. The events surrounding Apollo 13 and NASA at large help us place it into the context of the later 1960s and the early 1970s.

The Political context

NASA was founded on October 1, 1958, at the height of the Cold War, in order to answer the surprising success of the Soviet Union’s space program. Though the interest was growing, the setbacks from the Soviets not just launching the first satellite, but the first astronaut as well, caused some discouragement from politicians in Washington. However, Following President Kennedy’s challenge to land a man on the moon, the political will to commit to such a large project like Apollo was there. Throughout the 1960s, NASA would regularly receive sizeable amounts of funding from Congress, with NASA’s budget reaching a peak of nearly $56 billion in 1966. However, as soon as Apollo 11 landed on the moon, interest in the space program suddenly and sharply declined in Washington. Elected officials already needed to consider if NASA was worth the cost, as by 1970, the concerns of foreign policy and external military threats were now considered by the public to be on the backburner, and the increasing focus on domestic issues that were now dominating the headlines had moved forward. In fact, from the view of the public, the unpopularity of the costs when issues such as Civil and Women’s rights, as well as environmental issues, “only foreign aid [was] more unpopular than space exploration.”1 This downturn in interest also coincided with President Richard Nixon taking office in 1969. Nixon was not as enthusiastic about NASA as Kennedy or Johnson had been, opting to cancel Apollos 18-20, and nearly canceled all Apollo operations after Apollo 13, before being convinced to keep funding, but not before slashing NASA’s budget to a meager “$3 billion a year,”2 and pushed for NASA to focus on more practical missions, such as earth science and weather satellites. This shift meant that NASA would no longer be treated as a separate entity as it had been by Kennedy and Johnson, but instead a part of the executive branch that had to compete with other domestic interests.

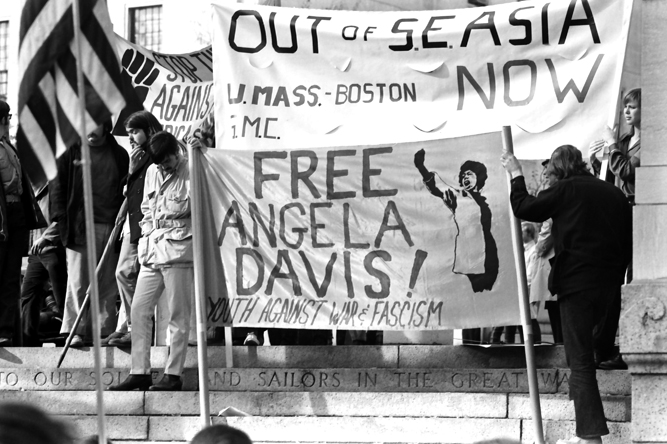

Racial and Gender Context

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the issues of Civil and Women’s Rights was brought into the limelight, particularly Civil Rights with the struggle of Black Americans fighting against the discriminatory Jim Crow Laws in the South. NASA as an organization came under criticism from Civil Rights activists, as NASA’s main facilities were predominantly located within Southern states, such as Cape Canaveral, Florida, Huntsville, Alabama, and Houston, Texas. Not only were the main facilities located within states rampant with discrimination, but NASA had regularly ignored such issues. While other Federal agencies began to implement equal opportunity programs, “no systematic program for civil rights in employment”3 was implemented by NASA. In fact, no program existed, because NASA was in an industry that was essentially entirely white. Though strides had been made since the 1940s, change moved at a snail’s pace, due to decades of racism and discrimination towards Black Americans in higher education, which was often needed for the various positions at NASA. Women also experienced similar treatment as well, with employment often being regulated to typists and clerks. Even with all these internal struggles, NASA still attempted to portray themselves to Congress as an organization that was in fact moving along with its equal opportunity program. However, internal reviews showed that “NASA’s actions about women and minorities badly lagged behind its words,”4 and those who were often hired through this program were often relegated to jobs with the lowest government pay scales. Such scandals tarnished NASA’s reputation in the public view, facing harsh criticism from Senate committees that were vital for funding.

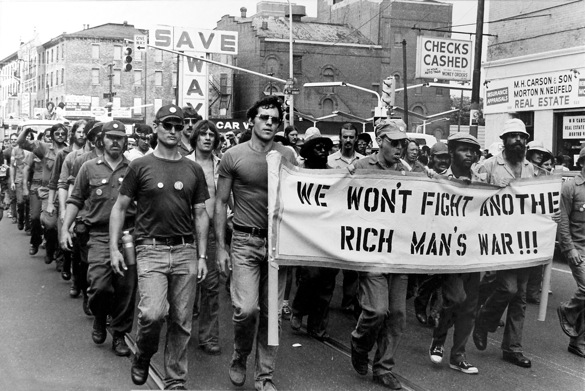

Vietnam

As the War in Vietnam continued to intensify throughout Johnson’s and Nixon’s Presidencies, NASA’s budget would receive a “cut of approximately $300 million in NASA’s requested allotment.”5 This cut meant several of NASA’s post Apollo ambitions, including concepts for manned missions beyond the Earth-Moon system. Meanwhile, opposition towards Vietnam grew with each day, and anti-war demonstrations grew increasingly popular as increasing military failures and reports of military misconduct dominated the headlines across the country.

- MCQUAID, KIM. “Race, Gender, and Space Exploration: A Chapter in the Social History of the Space Age.” Journal of American Studies 41, no. 2 (July 5, 2007): 408. ↩︎

- ReichsteinAndreas. “Space—the Last Cold War Frontier?” Amerikastudien / American Studies 44, no. 1 (1999): 133. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41157439. ↩︎

- MCQUAID, KIM. “Race, Gender, and Space Exploration: A Chapter in the Social History of the Space Age.” Journal of American Studies 41, no. 2 (July 5, 2007): 409. ↩︎

- Ibid, 419. ↩︎

- Divine, Robert A. “Lyndon B. Johnson and the Politics of Space.” Essay. In The Johnson Years, Volume Two: Vietnam, the Environment, and Science , 239. University Press of Kansas, 1987. ↩︎